The Other Half of a Heartbeat:

reflections on the death of my musical soulmate –

and supporting the love of my life through the same fate

By Julia Munroe Mandeville

There was a long stretch of time when music played in my head continuously and, by design, often from nearby speakers or instruments too. Early on, I harmonized to artists like Lauryn Hill and Sarah McLachlan, sang with a cappella groups and soloed on classics like Stand By Me by Ben E. King, and hummed alone and alongside to create tunes for lyrics I usually imagined in a quiet midnight. Later, the artists were like Florence Welch and Phillipa Soo, and Meghan and Casey and I formed a trio that wrote originals, and I lived in a melodious waterfall of sound.

So, the day her death rattle began and hours before Meghan would die at 34, Casey and I intuitively turned to music. Particularly, to I Wanna Dance With Somebody by Whitney Houston, our favorite both to prance around to and to cover – in this day’s version, with him on guitar and me on vocals, slowed way down into an acoustic ballad. Surrounded by candlelit altars we made with Meghan across weeks of hospice, we serenaded her with the reverence of knowing this was the last occasion the three of us would be together in song. We beamed as much as we cried. We played it twice.

Originally, our trio was a duo, with just me and Casey. We first came into orbit when I was on the board of a theatre company where he was musical director. We first performed during a grown-up talent show produced by an arts collective I co-founded called Emerge ABQ. All of our members were contributing an act, and I asked Casey to accompany me for We Are Young by .fun. When we finished to loving applause, he asked if I did any songwriting, and we set up a series of dates to compose.

Around our 6th or 7th session, Casey reflected that my voice might be resonant with a cello. I shrieked with delight, “My best friend is a cellist! She’s classically trained, and she hasn’t really been playing lately, but she does have her cello here, and I think she’d be curious to at least try.”

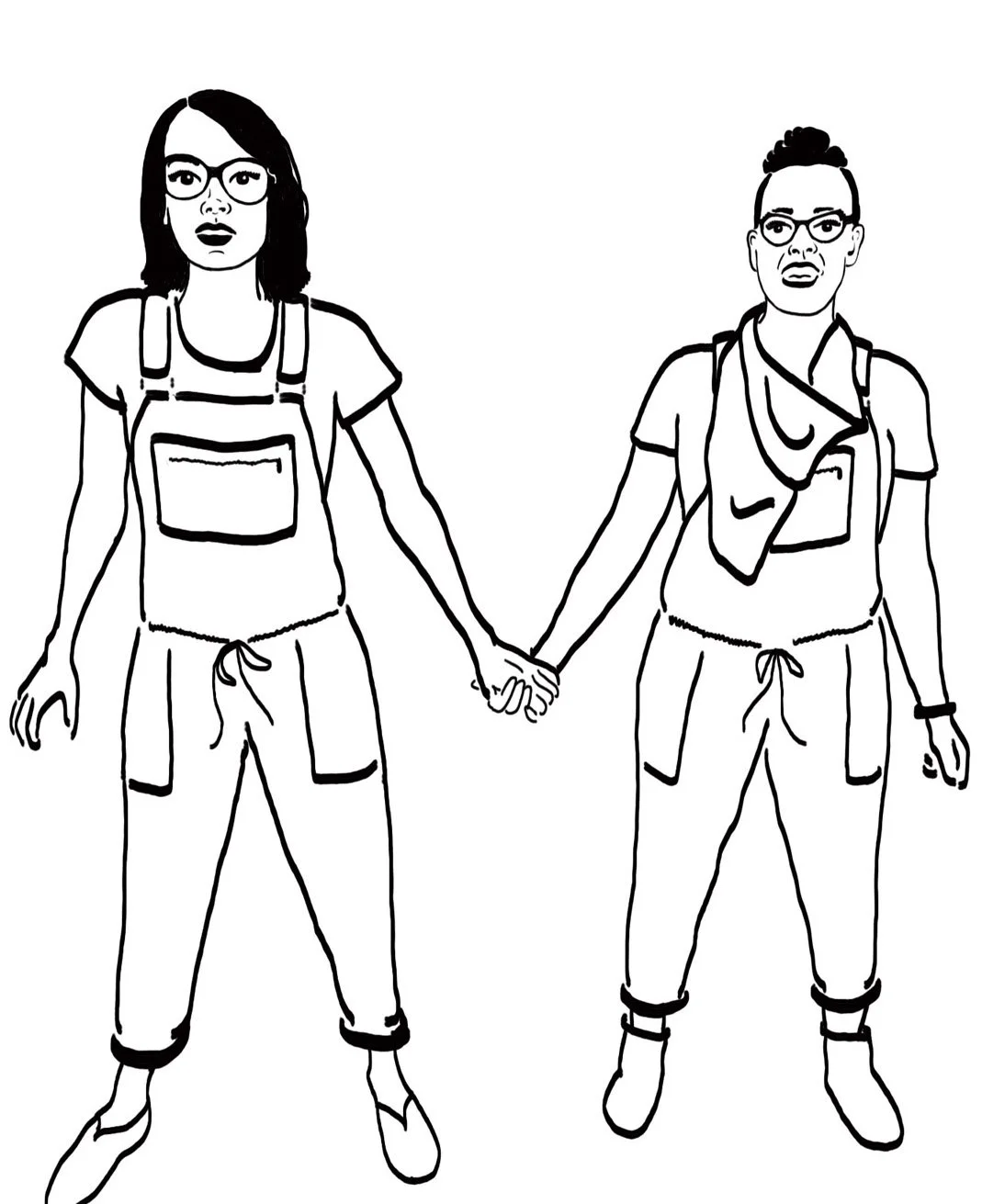

When Meghan arrived to our next practice, she and Casey shared an immediate gravitational pull. Within six months she moved into his low adobe house in Albuquerque, and within a year, they asked me to officiate their future wedding in the high desert forests of Taos. All the while, we wrapped ourselves in writing and recording our EPs, seeing shows by local and traveling bands, and organizing public events to feature other visual and performing artists of wildly different stripes. All along, from the shock of her diagnosis through her increasingly debilitating disease, Meghan requested we show up as her collaborators first and her caretakers second.

We agreed, and we fulfilled, though across the journey, the balance tipped back and forth. Once the doctors shifted from a treatment framework to a palliative approach, the scales fell over, and time narrowed under the weight. They introduced “terminal” to our lexicon in October and just that spring, after five weeks when Casey and I were her primary live-in caretakers, Meghan took her last breath in March. In the days after, as much to honor our grief as to protect ourselves from being swallowed by it whole, we made a pilgrimage to Northern New Mexico.

There, at a borrowed house with an indoor black stone fountain and a hand hewn coyote fenced yard, I wrote one more song, Everything That Glows, about witnessing Meghan’s spirit leave her body and transform into light. Then, in a stark and dramatic turn, the melodies I’d heard in my head for what felt like forever were gone, and my constant longing for music vanished. Casey and I never talked about it, but we gently stopped writing together, and now it’s clear that neither of us could bear the absence of our beloved’s cello lines. I went quiet, and the only trace I could find were the lyrics. At least the poetry stayed running through my mind.

Many of my other relationships changed in the aftermath, too. It was confusing for people, because I appeared the same – but I felt and behaved cellularly altered. Between Meghan’s death, a drawn-out divorce, and a physiological depression, I lost whatever thin capacity I’d pretended to have for hollow talk and imaginary drama. Some of my friends and collaborators leaned into this version of me, who almost exclusively explored major existential questions, and our bonds bloomed. Some wanted me to return to the work-hard-play-hard wild one who’d danced and drank until the sun rose every weekend, and as I could not comply, our ties fell away.

As a result, I grew more acutely aware of how I felt in the company of others. So come November, on my way home from a platonic dinner with James, I noticed the wish: That – were I to defy the logic of my past relational traumas and be open to a romance ever again – I would want My Person to engage me the ways James always had. To inspire the sense of belonging and reciprocity he drew out in me. To show up with the steadiness he offered throughout our friendship, across a whole decade’s highs and lows. With cinematic timing, my algorithm blared the pop banger Love You Like That by Dagny, and I realized this hint of wanting someone like him might mean I wanted exactly him.

In one of the single bravest acts of my life, I wrote him a letter saying so and asking if he might harbor any of the same inclinations, which I delivered to him by hand in the middle of his workday at the silk-screening business he owns. In one of the single weirdest acts of my life, when he tried to open the envelope in front of me, I conniptioned, “Oh god. Please, no. No! NO! That’s for looking at later when you’re alone at home,” before turning around and scurrying out the door. And then I waited.

The anticipation was painful and sleepless, tinged with just enough adrenaline to keep me from leaving my body entirely. Twenty four hours passed before I received word. By text, he reflected that he was pacing in nonstop circles, reading my letter over and over, trying to convince himself this was really happening – because, it turned out, he held a crush on me since we first met, but the stars hadn’t aligned for us to be single at the same time until this, and he’d never want me to feel anything but his highest respect and regard, so probably wouldn’t have made a move, and now was in awe of his luck.

We arranged to see each other in person the next night, where we affirmed that, in spite of our mutual terror, we wanted to try being together. We first kissed outside on a walk, under a leafy tree and a full moon. He sent me the video of Close Your Eyes by James Taylor and Carly Simon. My chihuahua mini dachshund rescue, Iris, fell enamored by him too. Since then, we’ve shared magnificent adventures and survived mind-bending circumstances – pandemics and wars, aging parents and dying peers, regressions of human rights and resurgences of fascist regimes. It is staggering to consider how much world happens within the span of one love.

My great loves with James and Meghan began the same way. Around the same time, I interviewed them (for different stories) as a weekly arts columnist for our local alt paper. Soon after, they joined me as founding members and lead artists with the Emerge ABQ collective. At an annual event we organized and dubbed Danger Carnival, Meghan co-created largescale temporary sculptures in unexpected places out of yarn, glitter, and light, and James headlined with drum and bass DJ sets, performing with his best friend and Junglist emcee, Patrick. They always brought the house up, down, up, down, up.

For a decade and a half, James and Patrick played under the moniker Rude Behavior. Their famously skilled sets and wild raves drew a loyal following to late nights. And then, in one day-job shift working on a film, Patrick was injured and subsequently prescribed opioids. In a too common trajectory, he cascaded into addiction. James tried again and again to intervene, but the substances proved stronger than Patrick’s will. Just as James reached acceptance and shifted focus from convincing Patrick to unconditionally caring for him, Patrick surprised everyone by checking into rehab – only for the withdrawals to fatally attack his heart at 40. James stood bedside when they turned off life support.

While cruel and unusual to both lose our best friends so young, I often marvel at how generous the universe was to weave us into navigating these journeys together. Solely *because* I’d experienced this specific brutality first, was I able to revere space and grace for James to mourn, to release the radical manifestations of his grief that I otherwise might’ve personalized, and to be patient enough for him to rebuild a sense of emotional equilibrium over time.

When James began to lament the secondary losses – the loss of his musical soulmate and thus, too, of his creative wellspring – I also understood firsthand. I offered him the story of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, which I learned from the miniseries Jazz, and which revealed to me an essential moral of self-compassion. The way I remembered it, when Parker died, Gillespie reflected a sentiment like, “Charlie was the other half of my heartbeat; how can I do anything without that?”

Still in the thick of my own melodic silence, I told James I didn’t know the solution, but did comprehend the process: The devastation never softens, but the capacity to carry it evolves, and gentleness is essential along the way. Being three years ahead of his death curve, I also promised I’d keep him posted. Just this summer, six years after my loss, I shared back further findings – (1) Everything That Glows was true, and Meghan not only turned to light, but also ritually takes shape in butterflies, beauties, and synchronicities, including my recently remade collaborations with Casey; (2) half a heartbeat still holds a rhythm; (3) music did come back to my every waking moment, finally returning to accompany the lyrics that moved through me all along.